The Art of Poetry And Translation: How The Disappearing OxReimagines a Buddhist Parable

by Aya Kusch

SEPTEMBER 20, 2020

The Disappearing Ox is available for $28 at Brilliantbooks.com

In the 1990s, the artist Max Gimblett suggested a novel yet intriguing project to the poet Lewis Hyde; that they create a modern, American version of the twelfth-century Chinese parable known as the Oxherding series. Hyde agreed, and from there emerged an odyssey into the realm of linguistic, visual, and conceptual translation.

This ambitious project, which would eventually become The Disappearing Ox, was built on the foundation of a decades-long artistic partnership between Gimblett and Hyde. Since they had met in 1990, they had collaborated on paintings, artist books, and works on paper. In the introduction, Hyde recalls visiting Gimblett in his studio in New York City, and how “when I would arrive, I’d usually find that he had covered the flat surfaces of the studio with large sheets of drawing paper and laid out pots of sumi ink… Max would place a brush in my hand, and he and I would proceed to fill the paper with words and images.”

Sumi ink is one of Gimblett’s signature mediums, and along with being a painter and calligrapher, Gimblett is also a Rinzai monk. His interest in Eastern art and Buddhism, paired with his history of a fascinating creative alchemy with Hyde, led them to begin working on The Disappearing Ox in earnest in 2002.

Chan Buddhism & the Oxherding Series

The Oxherding series first appeared in the eleventh century, and since then it has gone through numerous retellings. Over a series of ten drawings and poems, an oxherder loses his ox, finds and tames the ox, they are both “forgotten,” and in the final drawing we see the oxherder entering a village with open hands, ready to share his wisdom and compassion with others. He has cultivated these insights through disciplined meditation (or, to put it in the terms of the story, taming his ox), which has allowed him to find his true Buddha nature.

Not only does this story trace a path towards enlightenment, but it also reflects the values of one of the leading schools of medieval Chinese Buddhism, the Chan school. Chan Buddhism and the Oxherding series evolved alongside each other, and so it is unsurprising that the Oxherding series pulls in many of the characteristics of the Chan school: finding sacredness within the mundane, using art to express Buddhism’s wordless teachings, the importance of meditation, innate morality, and sharing knowledge. The idea of innate morality and finding fulfilment in the mundane are also Confucian beliefs.

There are many layers to this story. It is about an oxherder looking for his lost ox, but it is actually about cultivating a Buddhist practice. It is about a Buddhist practice, but it is also a glimpse of the history of Buddhism in China. Take it a step further, and you learn certain values in Confucianism.

Hyde and Gimblett’s task was to convey all of this while still making it resonate with a modern Western audience.

Creating Their Own Translation

So they took a bold, unconventional approach.

Instead of writing one version of each poem and passing it off as the closest approximation of the original, Hyde gives us three versions: his One Word Ox, where he replaces each Chinese character with its English equivalent; his Spare Sense Ox, which strings those words together to make it into a syntactically correct English sentence; and his American Ox, where he allows himself to take some creative liberties to create a poem that will perhaps feel the most familiar to American readers. In this way, he reveals the transformation that occurs during the act of translating, and the beauty that lies within the process.

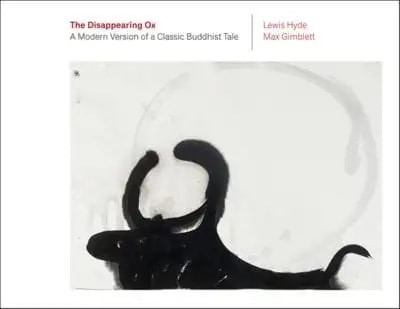

At the same time, Gimblett was creating his own visual translations. While the older artworks that make up the Oxherding series tend to be more figurative, Gimblett uses abstraction to bring the imagery to life with new energy. With spare yet expressive brushstrokes, his artworks are both meditative and exhilarating. His knowledge of Eastern art and extensive work with sumi ink are in conversation with Chinese traditions, but are not beholden by them. And when you look at his paintings, you can practically envision them spread across a studio floor, being painted on with thoughtfulness and intuition. You see the tale through his eyes, through his heart.

Take, for instance, his painting of a circle, or an enso, a common symbol for enlightenment. The ensoaccompanies the eighth poem, when the oxherder is deep into his Buddhist practice. The image is worth contemplating for a bit. At first glance, you can immediately see the spontaneity and movement: where the circle started and ended, when the brush began to run out of ink, and the spatters of ink that had strayed from his brush as he was painting. But it is also a perfect circle, one that can only be created after years of drawing hundreds of circles. And indeed, Gimblett once mentioned in an interview that it took him 15 years to get one that is round.

A common thread throughout Gimblett’s paintings is the measured balance between restraint and letting go, being intentional without sacrificing artistic expression, and respecting the past while embracing his more modern aesthetic. In this way, you can see how he and Hyde are the perfect pair: they are both care deeply about the process of translation, and about making this version of the oxherding series their own while still honoring what made the original story so enduring. Even as they took different approaches to translation, the book remains cohesive because their values are so clearly aligned.

In itself, this is a beautiful book of art and poetry, one that speaks multitudes about a fascinating era in Buddhist history. But the most compelling aspects may lie in a different story—one about finding joy within the beauty, complexity, and playfulness of translation.

The Disappearing Ox: A Modern Version of a Classic Buddhist Tale is published by Copper Canyon Press and will be available September 22, 2020.

AYA KUSCH is an editor, artist, and freelancer based in San Francisco. She grew up playing with mud, which eventually led to a love of clay and a subsequent BFA in sculpture. She is fourth generation Japanese and a third generation potter, a Bay Area native, and a former bookseller who still obsesses over the best way to organize a bookshelf. She loves good design, contemporary art that will worry your mom and confuse your dad, and sculptures that make you look up. She is currently working on a book about art from Edo Japan.